If is Evil

The current state of the world:

- People write

ifstatements into their code all the time - People spend a good portion of their time at work as software engineers finding the breaks in code, fixing broken code, and struggling to add new features without breaking old ones.

- People spend a significant amount of time refactoring and playing down technical debt

- People generally agree that SOLID principles should be followed (if you don’t know your solid principles, don’t admit that to me. Just look them up now. [If you disagree with SOLID, don’t admit that to me either]).

In short, software maintenance is difficult, and we know how to make it less difficult (by following SOLID), but people can’t seem to agree on how best to follow SOLID. In this post, I will argue that if you want your code to be SOLID, you should severely limit your cyclomatic complexity. I am not making the statement that lowering cyclomatic complexity will make code maintainable. I am making the statement that complex code is not maintainable, and that it is not SOLID. Some of the SOLID principles indirectly ask you to lower complexity. Other SOLID principles mitigate the negative side effects of following this advice.

First, let’s look at the behaviors that indicate that we are working with code that is too complex. If your codebase is complex, you will find yourself asking the same questions over and over again. Let’s assume you’re coding in Python today (because Python is awesome):

Questions associated with a program that is difficult to maintain

- What is the state of the program?

- How can I add new logic without affecting old logic?

What is the state of a program?

- The data bound to each variable.

This can be as simple as:

foo = 5

in which case we know that the variable has a value of 5. This rarely causes us to open a debugger. Here is a more typical (though simple) example

userMinAge = 5

if userIsLoggedIn():

userMinAge = 18

determineElegibility(userMinAge)

In this case, we do not know the value passed in to determineElegibility, because it depends on whether the user is logged in. We don’t necessarily know whether the user is logged in without entering a debugger. Here is another piece of information about the state of a program. Let’s talk about it in Java, because there is no escaping Java.

-

The concrete type of each interface

Here is a basic example:

interface Animal { public String speak(); } public class Dog implements Animal { @Override public String speak() { return "woof!" } } public class Person implements Animal { @Override public String speak() { return "hello!" } } public class Introducer(){ public String introduce (Animal animal) { return "the animal says" + animal.speak() } } -

The currently running line of code This is what you stop on when you set a breakpoint. Together, these three pieces of information are the entire application state at a point in time.

Why is it hard to add new logic without breaking old logic?

Logic interferes with itself. Adding new logic can impact the state of a variable at a point in time. It can impact which lines of code run at a given time. It can also introduce instances where the concrete type of an interface is not what would be expected.

How do we fix these things?

I’m glad you asked (yes you did). By following SOLID principles! I am not going to just rattle these off though. I want to talk about them as they pertain to if.

S - Single Responsibility Principle

Practice this at write time. When you make a new thing, make it single use. The most obvious and simple metric for this is to ensure that your code has a cyclomatic complexity of one. Responsibility is tough to define. That is why code that has a cyclomatic complexity of one may still violate SRP. Even so, eliminating branching in code will be a step along the road to achieving SRP.

Why is it bad to violate SRP by adding if statements?

Here is a simple Python example with branching code. There is an obvious issue with it.

if x == 1:

print "one"

else:

print "two"

This code will need to be edited eventually. Having two cases now means there will be more later. Don’t think that now is the only exception. Each time code is edited, there is a chance that a regression will occur. Additionally, adding more code to this class will make it more difficult to maintain, simply by virtue of the fact that the code will do more. If it is edited twice, chances of a break will compound. Additionally, what occurs under each case may grow. If that occurs, it is important for new code to be placed in the correct context. This is merely another place to make a mistake.

Well, I am glad that is settled. Let’s ignore the fact that I haven’t given an alternative to this code yet and just assume that you will blindly take my advice and remove branching, and also know exactly what to replace it with.

Let’s move on to the next SOLID principle.

O - Open/Closed principle

Classes should be closed for editing. That is, don’t edit classes. Just extend them, or make new ones. This fits nicely with Single Responsibility, as making an edit is likely to add a responsibility. This is especially true if that edit involves adding branching.

OK, done with that one too. This post is going really quickly. Wait, we are not done? You’re saying this is impossible? Fine, I admit open/closed is impossible. Therefore, for the approach I am suggesting, there must be a couple of exceptions. First, the obvious question.

Obvious question

If I can’t edit code, how do I tell my old code about my new code? The first approach that doesn’t explicitly break this rule is by using metaprogramming or looping through files to discover new code, but that is cheating. See: Jekyll discovering new blog posts.

The first kind of branching

There are a couple of types of branching. This type, I am going to call functional transform branching.

Functional Transform Branching

What if I am just formatting data? More scientifically, what if I am not branching for side effect, but am merely trying to do a functional transform on a discontinuous domain? Here is an example in Swift (for reasons to become clear soon):

func fizzbuzz(x: Int) -> String {

if (x % 15 == 0) {

return ("fizzbuzz")

} else if (x % 3 == 0) {

return "fizz"

} else if (x % 5 == 0){

return "buzz"

} else {

return String(x)

}

}

This code is trying to take in a number, find it on a graph, and return a value based upon that. The graph is all jumpy though. Here is a simpler to graph representation of fizzbuzz:

func fizzbuzz(x: Int) -> Int {

if (x % 15 == 0) {

return 100

} else if (x % 3 == 0) {

return 200

} else if (x % 5 == 0){

return 300

} else {

return x

}

}

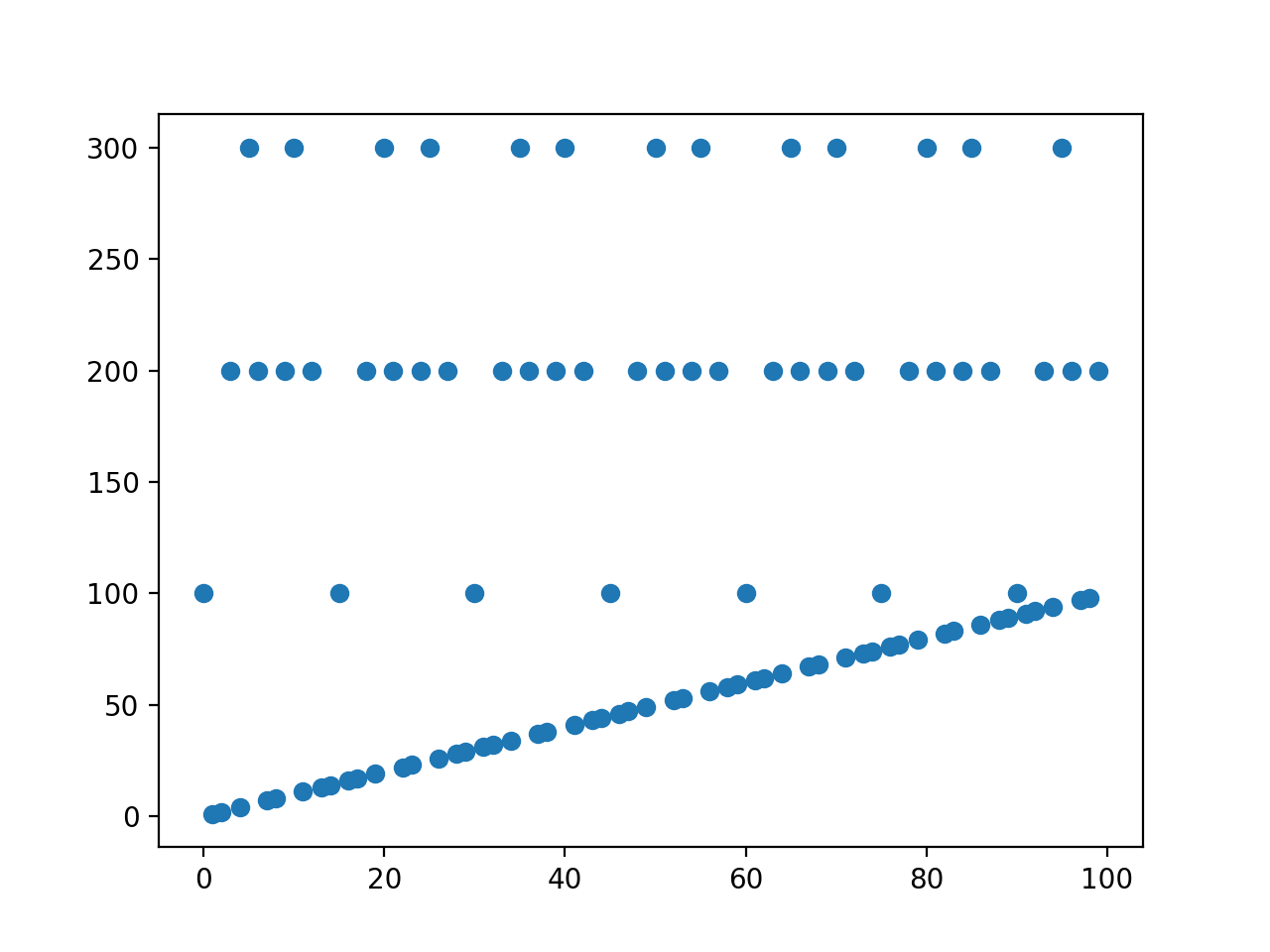

Here is the resulting graph for the first 100 points:

See how it is impossible to draw a smooth line to connect the points? This shows that you are implementing a piecewise function. In mathematics, piecewise functions are not implemented with if statements though. They are implemented by composing partial functions. Here is an example of implementing partial functions in Swift, using optionals.

func fizz(_ x: Int) -> String? {

if (x % 3 == 0) {

return "fizz"

}

return nil

}

func buzz(_ x: Int) -> String? {

if (x % 5 == 0) {

return "buzz"

}

return nil

}

func both(_ x: Int) -> String? {

if (x % 15 == 0) {

return "fizzbuzz"

}

return nil

}

func neither(_ x:Int) -> String {

return String(x)

}

func fizzbuzz(_ x:Int) -> String {

return both(x) ?? fizz(x) ?? buzz(x) ?? neither(x)

}

This is a partial function approach to solving the domain issue. Notice that in the event that the functionality is to be changed, only the fizzbuzz function will be altered. This makes the fizzbuzz function a sort of “code registry”. It breaks open/closed principle, but it does have a single responsibility: composing functions. Further, each partial function has a cyclomatic complexity of two, but the part of code that we are really concerned with is simply a domain and a predicate. Most importantly, the return value of fizzbuzz is not an optional. Therefore, it supports a full domain. In practice, we have taken one function with a complexity of four, and replaced it with four functions, each with a complexity of one or two, and a function registry with a complexity of four, bringing complexity from four to eleven. Nonetheless, we have bought something extremely valuable. We can add functionality to this code by creating a new partial function and adding it to the registry. We do not need to alter the partial functions. They are therefore compliant with open/closed. Additionally, debugging this code is mostly a matter of understanding what line of code is running. That is, which particular partial function is running in a given situation. This can be discovered by debugging the composing function.

Scala has more native support for partial functions than Swift. It successfully hides the bit that returns nil, but does not go all the way and make a function that takes in a domain. Check it out!

Another way to get around the issue of discontinuity is to break your domain apart and put it back together again at the end. If order doesn’t matter, this is relatively easy to do. One can simply filter out the parts of the domain that are not important for each sub-problem, and then smash all of the solutions together. If order matters, like it does in fizzbuzz, it becomes necessary to preserve the input with the result so that the data can be smashed together in a more organized fashion. Here is an example of this pattern in Haskell. Notice that there is no precedence to the filtering rules, so they each have to stand alone to select the exact domain necessary for each part.

module Fizzbuzz (fizzbuzz) where

import Data.List

fizzbuzz :: Integer -> [String]

fizzbuzz end =

let fizzes = zip (filter (\x -> x `mod` 3 == 0 && x `mod` 5 /= 0) [1..end]) (repeat "fizz")

buzzes = zip (filter (\x -> x `mod` 5 == 0 && x `mod` 3 /= 0) [1..end]) (repeat "buzz")

both = zip (filter (\x -> x `mod` 15 == 0) [1..end]) (repeat "fizzbuzz")

otherNumbers = filter (\x -> x `mod` 3 /= 0 && x `mod` 5 /= 0) [1..end]

numbers = zip otherNumbers (map show otherNumbers)

sorted = sortOn fst (numbers ++ both ++ fizzes ++ buzzes)

in map snd sorted

Alternatively, padding can be used to preserve place, and then the separate solutions can be merged with merging precedence rules:

module Fizzbuzz (fizzbuzz) where

fizzbuzz :: [String]

fizzbuzz =

let fizzes = cycle [Nothing, Nothing, Just "Fizz"]

buzzes = cycle [Nothing, Nothing, Nothing, Nothing, Just "Buzz"]

otherNumbers = [1..]

numbers = map show otherNumbers

sorted = zipWith3 zipFunction fizzes buzzes numbers

in sorted

zipFunction :: Maybe String -> Maybe String -> String -> String

zipFunction (Just fizz) (Just buzz) _ = fizz ++ buzz

zipFunction (Just fizz) Nothing _ = fizz

zipFunction Nothing (Just buzz) _ = buzz

zipFunction Nothing Nothing num = num

This solution is a bit redundant, as it is passing the strings for fizz and buzz around, when really all that is needed is some marker that it is not nothing, but it seems better to leave the literals out of the merging function. This second solution just returns all of the fizzbuzz numbers in order, so in order to be practical it should probably be prefixed with a take function.

The second kind of branching

Not all code is simply a matter of taking in data and returning data. That would be too easy. There is a reason this section is written in Swift, as side-effects are the bread and butter of mobile programming.

Branching for side effect:

First, blasphemy:

@IBAction func mainButton(sender: UIButton) {

switch sender.tag {

case SelectedButtonTag.First.rawValue:

println("do something when first button is tapped")

case SelectedButtonTag.Second.rawValue:

println("do something when second button is tapped")

case SelectedButtonTag.Third.rawValue:

println("do something when third button is tapped")

default:

println("default")

}

}

This is much better:

@IBAction func buttonOne() {

println("do something when first button is tapped")

}

@IBAction func buttonTwo() {

println("do something when second button is tapped")

}

@IBAction func buttonThree() {

println("do something when third button is tapped")

}

// default will never happen if there are three buttons

That was an easy fix! What if we are deeper in the code though?

@IBAction func buttonOne() {

doThing(1)

}

@IBAction func buttonTwo() {

doThing(2)

}

func doThing(x: Int) {

if (x == 1) {

println("I guess the first button must have been tapped")

} else {

println("I guess the second button must have been tapped")

}

}

That becomes:

@IBAction func buttonOne() {

doThingOne()

}

@IBAction func buttonTwo() {

doThingTwo()

}

func doThingOne() {

println("The first button must have been tapped")

}

func doThingTwo() {

println("The second button must have been tapped")

}

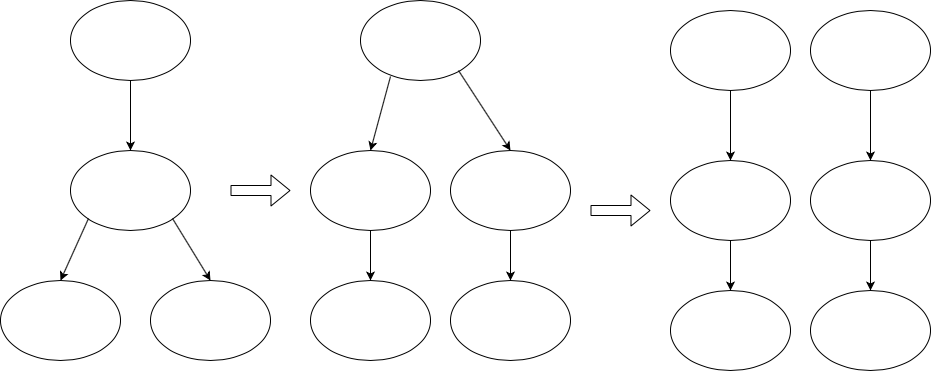

This strategy can be applied recursively until there is no branching anywhere in the code. You’ll end up “unzipping” the program like so:

That concludes this blog post.

But what about serial data, you ask? This code example deals with data that has to be parsed before the correct side effect can be chosen. First, the most obvious approach:

@IBOutlet age Int!

@IBAction func userDidTapContinueButton {

if (age > 17) {

println("WELCOME!")

} else {

println("GET OUT")

}

}

This seems impossible to fix. From a certain perspective, it is. We can give it an amalgam of the partial function treatment, though.

protocol RouterDelegate {

func userWasOldEnough

func userWasUnderage

}

class viewController: UIViewController, RouterDelegate {

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

router.delegate = self

}

@IBAction func userDidTapContinueButton {

router.route(age)

}

func userWasOldEnough() {

println("WELCOME!")

}

func userWasUnderage() {

println("GET OUT")

}

}

class Router {

public delegate: RouterDelegate?

public func route(_ age: Int) {

if (age > 17) {

delegate?.userWasOldEnough

} else {

delegate?.userWasUnderage

}

}

}

So we have replaced one class with a complexity of 2, with two classes, with a complexity of 1 and 2. Complexity has gone up. Even so, the code has become more flexible. Adding functionality is a matter of making a change to the router, and adding a method to the controller. This is analogous to creating a new partial function and adding it to a composing method. In this case, the router breaks open/closed but each method in the controller does not.

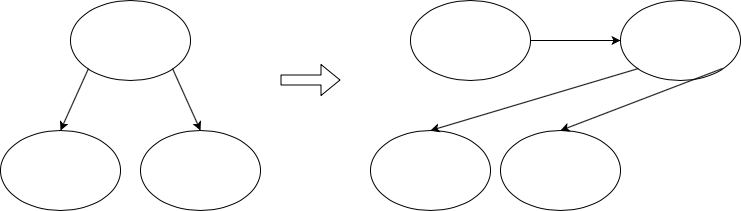

One controller may be called back to from a network router, a user input router, or any other router. It may even be called from multiple routers. If this approach is applied to the fullest extent, the number of callbacks in a controller will be equivalent to the number of unique pieces of functionality the view associated with the controller supports. Additionally, because there is no branching in the app besides inside of routers, and all methods from routers pass through controllers, controllers act as a nexus for all of the code in the codebase. A schematic of a large codebase following this pattern would look like a series of fuzzballs, with each ball being a controller, and all code coming out of the controller continuing in a straight line without branching. Below is a simple schematic showing the reasoning of moving branching from a controller to a router.

L - The dreaded repeated code

DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) is not a part of SOLID, but it is still a useful principle. One of the first concerns to come up with removing branching and making code comply with SRP is that, with everything split apart, a good deal of the code will be duplicated. In places where code used to live together, it now lives separately but has the same hobbies. This can be avoided easily by creating helper methods and classes that take an interface. Introducing interfaces and extracting repeated parts of code raises another concern soon after though - in fact, one that is raised at the beginning of this post under the section “What is the state of a program?”. This section points out that any section of code that uses an interface does not expose the concrete type that implements it without debugging or type checking. Fortunately, there is another SOLID principle to protect us from the downsides of this. Liskov substitution principle states that the supertype should be substitutable by the subtype. For the sake of simplifying software development by making the state of a program easier to understand, the concrete type should not matter. If it does, there is a violation of this principle.

I - But honoring Liskov Substitution Principle is hard!

Doubly fortunately, there is another principle to protect us from the dangers of working too hard while making sure we are in line when it comes to Liskov. That is (you guessed it) another SOLID principle. Interface Segregation Principle tells us that smaller interfaces are better than one big one. If interfaces are kept small, there are fewer methods in each interface to keep track of, and it is easier to honor the contract of each interface. Generally, if a Liskov violation is found, the first remedy is to split the interface.

Are you going to find a way to work each SOLID principle, in order, into this post?

Yes. D. Dependency Inversion principle asks for two main things:

- Dependence on abstractions, rather than concrete implementations

- The ability to re-compose or swap collaborators for any given object In practice, the first part of satisfying dependency inversion principle is rather simple if the other SOLID principles are kept. Code should be dependent upon interfaces in order to support enough abstraction to reuse code. Decoupling is an added benefit. Looking at Dependency Inversion with a focus on dependency injection points out a solution for a problem that had not been brought up: testing. Creating tons of tiny objects and having them arbitrarily composed together makes the code impossible to test if objects are being created in the middle of the consumers. Therefore, in order for the code to be testable, it must use dependency injection.

There are other benefits to having many tiny objects that can be arbitrarily composed. The most salient is that these tiny components can be reused in unexpected ways. As the codebase grows, new requirements will require the creation of new objects. If those objects require collaborators, many of those may already be at the ready, having been purpose-built for something else.

That’s beautiful. Now what if I am deep in legacy code?

- If you can’t go all the way with it, do this to just a section of the code. Start in a controller and call it a day. Any branching that takes place outside of a router should be split up until it ends up in a controller callback or a router that calls a controller callback

- If the branching occurs too deeply and you don’t want to commit, but you want to get some of the benefit, insert the strategy pattern. Branching occurs for one of three reasons.

- You need to transform data in a way that calls for a partial function

- You need to take serial data and perform different actions depending on domain (routing problem)

- You used to have clear code separation but now your code paths have collapsed (you have two different calls to the same function) If it is the last reason at play here, then set the appropriate state or function on a state holder in each caller to the function. This doesn’t have to be a direct call to the function, it can be an eventual call.

The benefit

Once all of the code is split apart, adding functionality is a matter of adding a new class to your code and adding a new callback. You don’t have to mess with the old code, you don’t break things, and you still get to reuse code because you broke out repeated sections of code into bits that just take an interface type. No more are the days of doing long, unexpected refactors at the beginning of each piece of work, because the code is already extremely flexible. Focusing on removing branching will drive the early SOLID principles, and refusing to suffer downsides for a more sophisticated architecture will drive the remainder. You’ll sleep better, and your hair will grow healthy and beautiful.